Colleen Boraca

Survivor

“We found a mass in your left breast that will require a needle biopsy for diagnosis.” Upon hearing this, I could hardly breathe. Two weeks earlier, I had my first mammogram at age 41. I fully expected to need a follow-up mammogram. That is fairly common, especially since I have dense breasts. My appointment for my second mammogram and ultrasound was on New Year’s Eve. I anticipated that with a few extra images, I could celebrate the arrival of 2019 after being told the mass was nothing to worry about. Unfortunately, that thought was naïve. The radiologist delivered the news that the mammogram and ultrasound did not provide clear results so the biopsy was scheduled for the following week. Why did this news knock the wind out of me? After a courageous six-year battle, my mother died of breast cancer in 2002. For years, my life was a roller coaster filled with hospitalizations, chemotherapy treatments, doctor’s appointments, and test results. 16 years later, I was instantly taken back to the fear of riding on this roller coaster. This time, however, I have a husband and three small children. How would a diagnosis impact them? Would I be around to see all the big (and little) events in the lives of my kids? All these thoughts were at the forefront of my mind while driving to my testing appointments, sitting in the waiting rooms, talking with the medical staff, and physically going through the testing. While I had previously been diagnosed with white coat hypertension, these emotions took it to a new level.

Throughout the process of being tested, I learned a lot. Here are some of the main lessons:

1) Order medical records. One of the nurses asked me what I knew about my mother’s cancer. Did I know whether it was ER or PR positive? Did she have HER2-positive cells? I had no idea. I was 19 years old when she was diagnosed. I knew other things. I knew that chemotherapy treatments made her so ill that she could not handle the smell of my Diet Coke in the car while driving home from the clinic. I knew that she cried when she got out of the shower, holding in her hands large clumps of hair as they fell out. I knew that we could not risk infection, preventing our family and friends from coming to our home the second week after one of her treatments because her white blood cell counts were so low. These were the things I knew about her cancer, not the characteristics of the disease. This realization prompted me to talk with my father about ordering my mother’s medical records. The laws addressing how to order the records of a deceased person vary by state. In Illinois, where I live, the records can be released to an executor or administrator of the deceased person’s estate or an agent appointed by the deceased person in a power of attorney for health care. If neither of these people exist, and the deceased person did not object in writing, the records can be released upon the written request of the individual’s surviving spouse. If there is no surviving spouse, the records can be requested by an adult child, a parent or a sibling of the deceased. My father obtained the medical records, and they arrived in mailbox. Be careful for the emotions that you face when reading them. I was not prepared to see the phrase “Referring patient to hospice care” and have not brought myself to read the rest of them. For now, I am relieved to have them as they may contain information that could help in the potential treatment of me, my daughter, my nieces or future generations.

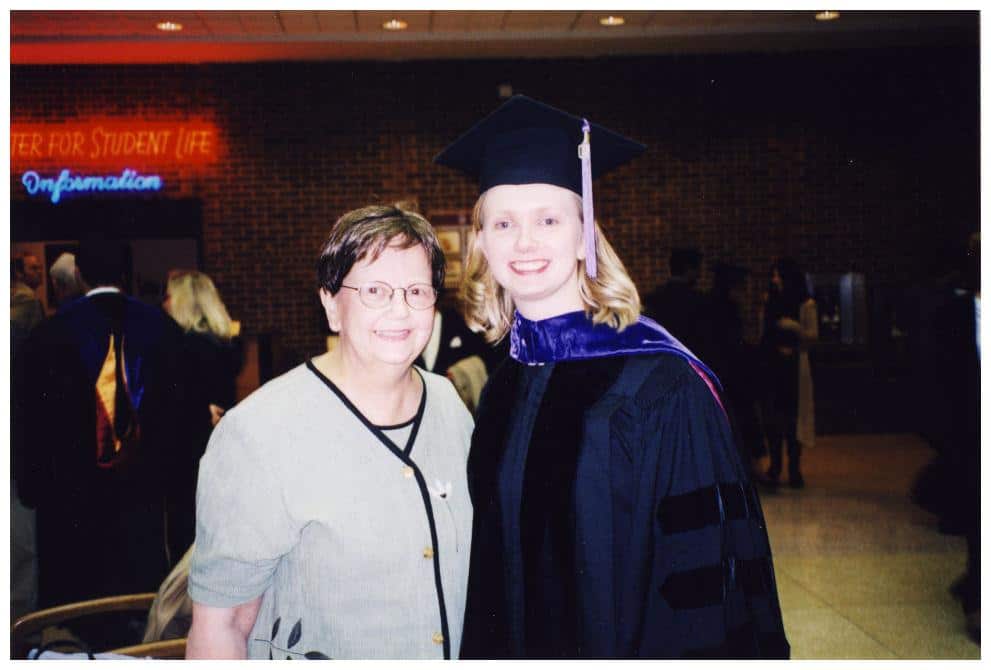

2) Own your history and emotions. Being tested for breast cancer should affect you differently if you have had a family member diagnosed with it. The best advice I received from a counselor after my mother’s death was to own my emotions. If you bury or ignore them, they will come back. It is okay to be totally terrified going through testing. I told every medical provider I dealt with that I was really anxious because my mom had died of the disease. Most seemed unfazed by it although a few were compassionate. I spent my spring breaks in college on the oncology unit at the Mayo Clinic, holding my mother’s hand while she was going through treatment. My children will never meet her. I am forever changed because of breast cancer, and the medical providers treating me should be sensitive how these experiences impact my ability to go through mammograms, ultrasounds and biopsies.

3) Research available medical care. Check out the experts in breast cancer by where you live. Are they covered by your insurance? My friends and I contacted our network of doctors, cancer survivors and advocates, finding a renowned breast surgeon who is in-network. What other services are paid for by your insurance? Under the Affordable Care Act, most insurance companies pay for BRCA testing and genetic counseling for people with a close family history as part of preventive care. Learning this information can be easier before you actually receive a diagnosis.

4) Keep busy. Waiting for medical appointments and test results can be excruciating, especially while the rest of the world does not know what is happening. Keeping busy helped. I planned the Christmas party for my daughter’s second grade class the day of my first mammogram. I spend most days working at a homeless shelter, and that was the best place for me. I realized that even if I had a diagnosis, I do have insurance, a home, a loving and supportive family, and a job with medical leave. Things can be put into perspective. When I had time to sit and think about what-ifs, my mind went to a dark place. I second guessed the advice I had been given to wait until now to have a mammogram. Most of all, take care of yourself. Spend time with people who bring you joy. I prayed. A lot. Know that you will not be operating at 100% throughout this process, and that is more than okay. As I sat in the waiting room before my biopsy, my sister-in-law sent me a text that said, “Remember to breathe.” It was good advice, back to the basics.

5) Stay positive. Even if you do receive a diagnosis, know that much is available in treatment options. Breast cancer is very different today than it was when my mother had it thanks to the hard work of organizations like the Susan Komen Foundation. Staying positive is certainly easier said than done, but attitude and outlook are so important. In the end, I was diagnosed with a benign condition. While not cancer, it definitely increases my chances of developing it. I set up an action plan. I will be meeting the surgeon I mentioned above. I will bring my mother’s medical records, and I will hopefully keep an open mind. Having a parent who has undergone breast cancer changes you forever. Because of this, it is okay to know that your experience of being tested for it is different from others. Do not let anyone tell you otherwise. Also, remember to breathe.